The article below came from The Legal Pad, Volume 4, Issue 3 (March 2020), pp. 3-8, published by Cyrus Gladden from the gulag in Moose Lake, Minnesota.

Excerpt from title rough draft “Master Document”

By Cyrus Gladden

Meaninglessness of and Lack of Protection from the Act’s Terms, “Impulse” and “Lack of Control”.

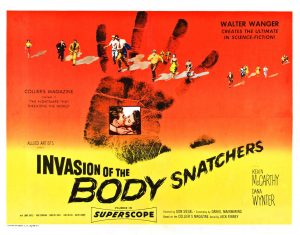

The Supreme Court spoke in Kansas v. Crane, 534 US 407,413, 151 L Ed 2d 856, 122 S Ct 867-(2002), of the need for “serious difficulty” controlling one’s “behavior.” Mary Prescott, “Invasion of the Body Snatchers: Civil Commitment after Adam Walsh,” 71 U. Pitt L. Rev. 839, 851 (Summer 2010), explains, ” … [T]he Crane decision does impose a duty on prosecutors to establish proof of ‘serious difficulty in controlling behavior.’ (Crane, ibid) …. Crane essentially served to limit the Hendricks decision to its own facts.”

Surely, in this statement, the Supreme Court did not mean to include within that explanation of lack of volitional control those who have perfect volitional control, but who deliberately decide to commit a crime and then plan (often at length) how to optimize their chance of getting away with it. This scenario is purely a matter of criminal behavior.

Thus, 1as to pedophilia – commonly misperceived as uncontrollably impulsive, Ryan C. W. Hall & Richard C. W. Hall, “A Profile of Pedophilia: Definition, Characteristics of Offenders, Recidivism, Treatment Outcomes, and Forensic Issues,” Mayo Clin. Proc. 2007: 82(4): 457-471 (2007), at p. 462, elucidates to the contrary: “… The fact that 70% to 85% of offenses against children are premeditated speaks against a lack of perpetrator control.” (emphases supplied).

Yet Michael Barzee, “Fifteen Years and Counting: The Past, Present, and Future of Missouri’s Sexually Violent Predator Act,” 82 UMKC Law Rev. 513 (Winter 2014 ), at p. 526, provides this analysis:

” … An offender cannot at once choose to engage in behavior ( culpability) and at the same time be unable to control it (volitional impairment). In essence, the legislature wants a person who has committed a sexually violent crime to be treated during the trial phase as having volitional control over his behavior… However, when the convicted sex offender nears the end of his prison sentence, the legislature wants him to be treated as though he does not have volitional control and should therefore be civilly committed and treated. Thus, the legislature is having it both ways, which goes against legal reasoning that a person is either in control or not in control of their behavior.”

Julia C. Walker, “Law Summary, Freedom Is to Confinement as Twilight Is to Dusk: The Unfortunate Logic of Sexual Predator Statutes,” 67 Mo. L. Rev. 993 [2002], at 1013)”

Eric W. Buetzow, “Ignoring the Supreme Court: State v. White, The Civil Commitment of Sexually Violent Predators, and Majoritarian Judicial Pressures,” 58 Hastings L.J. 413 (December 2006), explains the flaw in logic of state court decisions holding that no finding of fact is required on the issue of “serious difficulty in volitional control by a sex offender on trial for commitment:

p. 415: “I. State v. White[, 891 So.2d 502 (Fla. 2004)]: A Convenient Interpretation of Crane ” An essential element was whether or not White had serious difficulty controlling his behavior, an element required, the appellate court reasoned, by the United States Supreme Court ‘s holding in Crane. In 2004, the Florida Supreme Court granted review, giving itself occasion to consider whether Crane indeed required a finding that the defendant had serious difficulty controlling his or her behavior.”

p. 415-16: “In a four-to-three decision, Florida’s high court reversed the appellate court ruling and held that the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision in Crane did not require such a finding and thus jury instructions on this point need not be given. [Id at 509] In other words, the court in White refused to concede that Crane compelled an explicit volitional impairment finding for the civil commitment of sex offenders in its state. However, after the Supreme Court’s decision in Crane, how does the White Court justify this result?”

p. 416: “Problems in Reasoning “Principally, the court in White proffers what appears to be a ‘same result’ or ‘functional equivalent’ rationale. That is, that Florida’s sexually violent predator statute will in effect only net sexually violent offenders who have difficulty controlling their behavior, thus negating the need for an explicit finding on volition.

“The court reasoned- Although the Ryce Act does not state the standard in terms of whether the respondent has serious difficulty controlling behavior, it accomplishes the same result. The respondent must suffer from a “mental abnormality,” which predispose him to commit sexually violent offenses. Moreover, the respondent must be “likely to engage in acts of sexual violence,” which means that “the person’s propensity to commit acts of sexual violence is of such a degree as to pose a menace to the health and safety of others.”

One who fits such a description necessarily will have difficulty controlling his behavior. The terms in the statute, when taken together (if not independently) comply with the requirements of Crane.’ [Id at 509-10 (quoting Section 394.912)]

“But this view of Crane is problematic on multiple fronts. First and foremost, it is difficult to adopt such a conception of Crane given the U.S. Supreme Court’s statement that ‘[w]e do not agree … that the Constitution permits commitment of the type of dangerous sexual offender considered in Hendricks without any lack-of-control determination.’ [Crane, 534 U.S. at 412]

“Furthermore, the mere ‘difficulty’ of controlling behavior that the White Court depicts is undoubtedly less demanding than the standard actually articulated in Crane, which requires that there must be proof of serious difficulty in controlling behavior.’ [Id at 413] And, not surprisingly, there is no mention by the Supreme Court in Crane of a ‘same result’ exception that would enable state courts to forgo a lack of control determination.” [534 U.S. at 407].

at p. 416-17: “There is no confusion within the Supreme Court as to what the holding in Crane demands. In addition to the majority’s language, Justice Scalia clearly articulates, today’s opinion says that the Constitution requires the addition of a third finding … that the subject suffers from an inability to control behavior.’ [Crane, 534 U.S. at 423 (Scalia, J. dissenting). Justice Scalia’s dissent attacked the correctness and wisdom of requiring proof of volitional impairment, thereby implicitly confirming that imposing this requirement was exactly what the majority opinion accomplished. Id at 421-22.]

at p.417: “Specifically, the White Court’s view requires a leap in logic that the Court in Crane was not willing to make. Under Crane, one who suffers from a mental abnormality or personality disorder and is deemed likely to commit future acts of sexual violence cannot be said to necessarily suffer from serious volitional impairment, nor is the perceived likelihood of committing future acts necessarily because of a volitional impairment. … [A] defendant may suffer from a mental or personality disorder that has the effect of predisposing him or her, at some level, to re-offending, yet simultaneously be able to control his or her behavior to a high degree. Such a person may nevertheless be found by a jury to be ‘likely’ to commit future acts of sexual violence. “Yet under a logical reading of the majority view in Crane, a person who fits this description would not be eligible for civil commitment.”

at p. 418: “Recall that in Crane, just as in White, the jury made affirmative findings that (1) the defendant sex offender suffered from a mental abnormality or personality disorder, and (2) his condition rendered him likely to commit future acts of sexual violence. Unlike the White court, the court in Crane was clearly unwilling to infer the existence of volitional impairment simply from these findings. Instead, it vacated and remanded the case with instructions that ‘there must be proof of serious difficulty in controlling behavior.’ This move demonstrates that Crane requires states to add additional protections beyond those already implicit in their SVP statutes.”

Right here Buetzow cites in a footnote to Pfaffenroth, “The Need for Coherence: States’ Civil Commitment of Sex Offenders in the Wake of Kansas v. Crane, 55 Stan. L. Rev. 2229, at 2248 (2003).

Continuing on the main body at pg.418:

“The original Crane instructions contained a substantive definition of ‘likely,’ which was defined as ‘more probable to occur than not to occur…The Court ultimately rejected a view of Hendricks and the Constitution that would permit different judicial treatment for mental impairments already thought to necessarily be of a volitional nature.”

Kenneth W. Gaines, “Instruct the Jury: Crane’s ‘Serious Difficulty’ Requirement and Due Process,” 56 S.C. .L. Rev. 291 (Winter 2004), explains in more depth thus:

at p. 300: “The trend of state appellate courts, with Justice Scalia’s blessing, has been to ignore Crane. Most state courts have maintained that their civil commitment laws already commit only those who lack significant volitional control because of the nexus between the targeted disorder and the offender’s acts that ‘necessarily and implicitly involves proof that the person’s mental disorder involves serious difficulty for the person to control his or her behavior. These states concede that Crane requires determination of some lack of control before the state can civilly commit an offender. However, these states argue that Crane does not require a specific jury finding that a respondent lacks volitional control, because the Court in Crane upheld the commitment in Hendricks as constitutional despite the absence of any specific jury determination of lack of control. … Minnesota … [has] adopted this interpretation [ citing In re Ramey, 648 N.W.2d 260, 266-67 (Minn. App. 2002) (noting that the Minnesota statute in question implicitly includes a finding of “serious difficulty”]. These state court decisions are contrary to the Court’s determination in Crane, which required specific proof of ‘serious difficulty controlling behavior.”‘

at p. 316: “The unpublished case of In re Martinelli, [2000 Minn. App. LEXIS 973 (Minn. App. 9/12/00)] can dispel any lingering doubt about Crane’s meaning. The United States Supreme Court, after granting certiorari, vacated the Minnesota court’s opinion [Martinelli v. Minnesota, 534 U.S. 1160 (2002)]. The Minnesota court had relied on the reasoning of a 1999 Minnesota Supreme Court case [In re Linehan, 594 N.W.2d 867 (Minn. 1999)] to read into the Minnesota statute an implicit lack of control instead of requiring proof of a lack of control as a separate element that the state had to prove for civil commitment of an SVP. [In re Martinelli, 2000 Minn. App. LEXIS 973, at *4-5 (citing In re Linehan, 594 N.W.2d at 867).] The Supreme Court remanded the case for reconsideration in light of Crane. [Martinelli, 534 U.S. at 1160.] On reconsideration, the Minnesota Court of Appeals recognized that Crane requires a specific finding of lack of control based on expert testimony tying that lack of control to a properly diagnosed mental abnormality or personality disorder before civil commitment may occur.’ [In re Martinelli, 649 N. W.2d 886, 890 (Minn. App. 2002)].

” … The Supreme Court ordered the Minnesota and Illinois Courts to apply Crane’s volitional control standard as new law. Thus, Crane is distinguishable from Hendricks, because Crane creates new law requiring a separate finding of lack of volitional control as an additional element of proof from which a court or jury is to make a decision.”

Nothing in Crane or in any other Supreme Court case provides justification for any proposition that the meaning of the United States Constitution has been surreptitiously changed to authorize supplanting the inviolate role of criminal law by such a sweeping use of preventive detention and forced mental treatment of those thought likely to be tempted to commit crimes for such general “criminal thinking.”

To avoid this unintended slide into an end to all criminal procedural rights, that passage from Crane must be read with “behavior” as referring to behavior in a given moment of opportunity without any such advance planning or premeditation, and “serious difficulty” must be read as limited in reference to such difficulty in controlling one’s involuntary response to an impulse to commit a criminal sexual act at that moment. Indeed, this view is confirmed by the explanation offered for the Crane majority by Justice Breyer, at 534 US 413, that ” … a critical distinguishing feature of that ‘serious … disorder’ [as discussed in Kansas v. Hendricks] consisted of a special and serious lack of ability to control behavior.”

In Hendricks, at 521 US 374, Justice Breyer stated that

“… Hendricks suffers from a classic case of irresistible impulse, namely, he is so afflicted with pedophilia that he cannot ‘control the urge’ to molest children;”

Illustrating how this is to be applied, Justice Breyer, writing for the majority in Crane, continued, at 534 US 414-15:

“Hendricks himself stated that he could not ‘control the urge’ to molest children. 521 U.S. at 360, …. … [O]ur cases suggest that civil commitment of dangerous sexual offenders will normally involve individuals who find it particularly difficult to control their behavior.”

This statement is consistent with the concept of inability in the moment to control an impulse, but is inconsistent with the idea that someone merely has a predisposition to commit crimes of a given sexual type generally. Any broader reading of the requirement for “serious difficulty” sends American law inexorably down the path of sacrifice of all personal rights at the altar of a new “preventive state” of overriding power over all individuals, with the right to invade one’s innermost thoughts and ‘ secret temptations and to confine one indefinitely in an attempt to eradicate such thoughts and temptations. This is not just madness, it is the ultimate form of tyranny. In its June 15, 2015 Order, this Court opined that some MSOP detainees “are truly dangerous and should remain confined at the MSOP, but for whom constitutional procedures must be followed” (Id. p. 70).

MSOP detainees all know that the only true standard of such dangerousness for commitment purposes is whether one so utterly lacks control of his own actions in the moment (volitional impairment) that, in that moment, he certainly will act upon an impulse that he simply cannot resist. Only a few among all 730 who now still survive in MSOP can be fairly argued to lack such self control. Because that standard of lack of volitional control is already within the parameters of commitment under Minnesota’s commitment law for those who are “mentally ill and ‘ dangerous,” and since such compulsion to act on an impulse is defined as a symptom of mental illness, those: few can be committed under that statute; there is no need for a commitment statute specific only to sex offenders.

On the contrary, sex crimes are almost always the subject of extensive pre-planning and even long-term preceding actions (think: grooming, for instance) aimed at setting up an ideal opportunity for the crime(s) to follow. No matter how deplorable anyone finds that conduct, it is the absolute antithesis of lack of self-control. While one may argue that such deviousness and plotting call for harsh criminal penalties, it is illogical to argue that such cunning shows impaired volitional control. Thus, the resistance to .mass release of the rest of us, who never had any such problem of control of our actions in any situation, is clearly the product of emotional reaction, rather than any process of dispassionate reasoning. In point of fact, “the line between an irresistible impulse and an impulse not resisted is probably no sharper than that between twilight and dusk.” (Kansas v. Crane, 534 U.S. at 421).Short of a persons’ own admission that he cannot control his criminal sexual behavior, there is no scientifically accepted means of any certainty of deducing such lack of ability to control such behavior.

Jennifer S. Jason, “Beyond No-Man’s Land: Psychiatry’s Imprecision Revealed by Its Critique of SVP Statutes as Applied to Pedophilia,” 83 So. Cal. L. Rev. 1319, 1349-50 (2010), explains that the Supreme Court’s decision in Kansas v. Crane, supra:

“Did not give guidance as to a specific definition of “lack of control,’ stating that ‘inability to control behavior” will not be demonstrable with mathematical precision. It is enough to say that there must be proof of serious difficulty in controlling behavior. After Crane, it is now unclear what the notion of volitional control means. Lower court cases since Crane have articulated contradictory standards relating to volitional impairment, and there is no clear standard for what qualifies as inability to control. Although Crane suggests that the SVP evaluations for offenders convicted of having sex with a child consist of three distinct requirements: (1) mental abnormality (pedophilia), (2) volitional impairment, and (3) dangerousness, in practice the volitional impairment component has been collapsed into either the mental abnormality requirement or the dangerousness requirement. The assumption of volitional impairment based on a diagnosis of pedophilia appears rarely used. More often, the volitional impairment step is collapsed with the dangerousness step and thus a statistical risk assessment analysis is used…Risk assessment measures … essentially are a measurement of sexual acts.”

Norman J. Finkel, “Moral Monsters and Patriot Acts: Rights and Duties in the Worst of Times,” 12/2 Psychology, Public Policy, and Law 242-277, at 255 (2006), observes:

” … Reviews ( Grisso, 2003; Melton, Petri/a, Poythress, & Slobogin, 1997: Nicholson, 1999; Wrightsman & Fulero, 2005) of the prevailing forensic assessment instruments have found that despite improved reliability, there is no valid test to measure whether or not an individual can or cannot control his or her impulses. Normatively, the problem has been that when experts proffer qualitative conclusions that these defendants cannot control their impulses, they are, in effect, impermissibly answering the ultimate opinion question that falls within the jury’s province while their answers seem to violate the legal standards for admitting expert testimony.”

As Jackson, Rogers, and Shuman, “The Adequacy and Accuracy of Sexually Violent Predator Evaluations: Contextualized Risk Assessment in Clinical Practice,” 3 International Jour. Of Forensic Mental Health 115-129 (2004)] observed, ” … no variables on either the actuarial methods or the structured clinical methods allow the clinician to draw conclusions regarding the volitionality of the offender’s behavior’ (p. 26)” R. Prentky, E. Janus, et al., “Sexually Violent Predators in the Courtroom: Science on Trial, 12 Psychology, Public Policy, and Law 357, 364 (2006).

Of course, statistical analyses can say nothing about a given individual’s lack of volitional control. Actuarial methods may attempt to categorize the offender and to apply a past statistic of recidivism by others to him. The inaccuracy and inherent uncertainty of this method is addressed supra. However, even assuming accuracy and certainty, a prediction of commission of a sex crime in the future cannot say whether such commission would be a result of inability to control a momentary strong impulse, or simply a deliberate act, perhaps one planned for months in advance. Only the former would offer support for an SPP/SDP commitment. Contrary to Jason’s generalization, Minnesota appellate decisions more frequently attempt to rely on a diagnosis of pedophilia as presumed to inherently imply a lack of control. As is discussed infra, that presumption is a baseless non sequitur.

Eric S. Janus, “Sex Offender Commitments: Debunking the Official Narrative and Revealing the Rules-in-Use;” 8 Stanford Law and Policy Review 71, 81-82 (Summer 1997) observes that :

“[t]his concept of ‘volitional dysfunction’ has consistently baffled judges, forensic professionals, and philosophers. At Footnote 166, Janus quotes Stephen J Morse, “Causation, Compulsion, and Involuntariness,” 22 Bull. Am. Acad Psychiatry Law 159, 166 (1994):

“No consensus about involuntariness exists among ‘experts’ or laypeople. Although many forensic psychiatrists and psychologists (and lawyers) assume that they possess a good account of involuntariness and of so-called pathologies of the will and volition, no satisfactory and surely no uncontroversial account of any of these topics exists in the psychiatric, psychological, philosophical, or legal literatures.”

(Eric S. Janus, “Sex Offender Commitments and the ‘Inability to Control’ – Developing Legal Standards and a Behavioral Vocabulary for an Elusive Concept” Chapter 1 in: The Sexual Predator: Legal Issues. Clinical Issues, Special Situations (Vol. II) Anita Schlank, ed. (Civic Research Institute, Kingston, N.J. 2001), at pp. 1:8-1:9) “APPLICATION TO SEX OFFENDERS”

“Caused Behavior… We should not use the concept of ’caused behavior’ as a defining characteristic of inability to control, as this concept is often confused for the latter. It is assumed that if certain behavior is ’caused’ by a given psychological condition, then the person had no ‘control’ over the behavior. But this approach proves too much. All human behavior is ’caused,’ but we nonetheless insist that humans have control over their behavior, at least in general. It may be that we will want to· say that certain kinds of ’caused behavior’ evidence inability to control, such as a behavior ’caused’ by a particular kind of mental disorder. But then the real work will be done by our characterization of the mental disorder, not by the attribution of causation.”

And just as being ’caused’ does not make behavior beyond an individual’s control, so too being ’caused by a mental disorder’ does not ipso facto justify that ascription:

“The fact that an individual’s presentation meets the criteria for a DSM-IV diagnosis does not carry any necessary implication regarding the individual’s degree of control over the behaviors that may be associated with the disorder. Even when diminished control over one’s behavior is a feature of the disorder, having the diagnosis in itself does not demonstrate that a particular individual is (or was) unable to control his or her behavior at a particular time.”‘ [Note 41: American Psychiatric Assn., Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders ( 4th ed. 1994 – “DSM-IV”); also stating, at Note 40, that “the notion that given behavior is ’caused’ by a mental disorder is itself an extremely problematic conclusion to draw,” citing: Virginia Adige Hiday, “Understanding the Connection Between Mental Illness and Violence,” 20 Int ‘l J L. & Psychiatry 399, 412 (1997)]

“The Strong Impulses Model “Impulsivity; Antisocial Personality “. The typology of sex offenders Hudson et al. developed includes types that are inconsistent with the strong urges paradigm and makes distinctions between ‘appetitively driven’ offense pathways and ‘impaired-regulation’ models of offending. The most frequent type they describe does not fit into the strong urges paradigm because it entails a positive attitude toward offending, involves explicit decisions to offend, arises out of a basically happy affective state and, after the offense, concludes with a commitment (to self) to continue the offending behavior. This description does not fit with the typical ‘strong urges’ model because there is no growing internal pressure to act, no attempts to control, and no regret or feeling bad afterwards. Rather than representing an impaired ability to control behavior, this pathway, in Hudson et al. ‘s description, represents an example of ‘expert’ or skilled performance.

“Paraphilia in the DSM-IV definition is characterized by ‘recurrent, intense sexual urges, fantasies, or behaviors … [that] cause clinically significant distress or impairment in social, occupational, or other important areas of functioning.’ This definition accommodates intense ‘urges’ but could be satisfied by ‘intense behaviors’ as well, and says nothing about failed attempts to control the urges.” (Id, p. 1 :13)

“The Problem of Offender Acquiescence to Impulses ” … The normal ‘bias’ in self-reporting is to minimize responsibility by disclaiming the ability to control. In their study of convicted rapists, for example, Scully and Marolla found that 83 percent of their subjects viewed themselves as ‘nonrapists.’ More than half of those, while admitting their involvement, ‘explained themselves and their acts by appealing to forces beyond their control, forces which reduced their capacity to act rationally and thus compelled them to rape.’ [ emphases supplied] ” … As Baumeister et al_. put it with respect to the unsuccessful dieter: ‘Someone may claim that she cannot control her eating, but do her jaws really move up and down to chew the food against her will?’ …. ‘Although it is very difficult to obtain decisive empirical data regarding the issue of acquiescence, we suspect that acquiescence is the norm, not the exception. It is rare that human behavior is the result of inner forces that the person is entirely helpless to stop or control.’ [ emphases supplied]

” … Of course, the mere fact that there is acquiescence does not mean that the inability-to control ascription is inapposite. Rather, the presence of acquiescence simply highlights what I have argued earlier, that the standard for a judgment of inability to control contains a heavily normative, or moral judgment.” (Id, pp. 1: 14-1: 15)

“It is our view that sexual offenders are not suffering from any disease and that their behavior is not out of their control…. In fact, it is clear from an examination of the behavior of these men that their offending is very well controlled.’ [W.L. Marshall, et al., “Present Status and Future Directions,” in Handbook of Sexual Assault: Issues, Theories & Treatment of the Offender 389, 391 (W.L. Marshall, et al., eds., 1990)] “Pithers agrees: “‘Offenders are informed that urges do not control behavior. Rather, giving into an urge is an active decision, an intentional choice for which he is responsible.”‘ [William D. Pithers, “Relapse Prevention with Sexual Aggressors: A Method for Maintaining Therapeutic Gain and Enhancing External Supervision,” in Handbook of Sexual Assault: (etc.), supra, 343, 345] [Id., p. 1: 16; emphases supplied]

[Note 175 adds that: “Prentky et al. state that planning the offense is one of the most frequent precursors to offenses by child molesters, being exhibited by 73 percent of the sample in one study. See: Robert A. Prentky et al., Child Sexual Molestation: Research Issues (U.S. Dept. of Justice, June 1997) at 8.” Thus, e.g., Janus, “Sex Offender Commitments and the ‘Inability to Control ‘ – Developing Legal Standards and a Behavioral Vocabulary for an Elusive Concept,” supra, at 1: 19, describes a “pathway “to sex offending identified by Ward and Hudson as “approach-explicit”, which “involves ‘conscious, explicit planning and well-crafted strategies that result in a sexual offense.’ This pathway involves competent self-regulation but ‘inappropriate, harmful’ goals, standards, and attitudes.”]

“Let us consider a sex offender who falls into Ward and Hudson’s approach-explicit category, an offender who desires to continue abusive sex and actively plans for it. How should we classify this person with respect to control capacity?”

There are two sound reasons for refusing to ascribe an inability to control. First, this person exhibits self-regulation skills rather than a self-regulation deficit. He has characteristics that we associate with deliberate, under-control behavior, such as careful planning and explicit decision making. Second, because he desires to continue offending, there is an absence of evidence from which one could conclude that he lacks the capacity to control his behavior. Since he has not yet tried hard to stop, we have no basis for judging whether he could refrain from offending if he tried ‘hard enough.’ The only potential basis for ascribing an inability to control to this person is that his offending is so much a part of his personality, so ingrained in his values and personal goals, that he ‘could not act otherwise.’

“This, of course, is a rhetorical move that could be made with anyone at any time. We are all, after all, who we are. If we say that the pedophile lacks the ability to control his behavior because his behavior is determined by his personality, then we must say that we all lack that ability. This is a dangerous rhetorical move because it undercuts the general assumption of free will and moral responsibility, absolving the individual of responsibility for his or her own character.” (Id., pp. I :20-21 ; emphases supplied)

“Meeting the Constitutional Criteria … As a general matter, the kinds of self-regulatory failure that characterize sexual offending do not narrow the group eligible for civil commitment, and do not provide a means of distinguishing sex offenders from the great mass of other criminals. In fact, the impulsivity that marks many sex offenders is the hallmark of general criminality. Further, though the consequences of self-regulatory failure among sex offenders are horrendous, [such failures compare to] failures that impair people’s ability to obey the law, quit smoking, lose weight, stop gambling, or achieve any difficult, long-horizon goal. As Baumeister et al. observe, ‘Self regulation failure has been implicated as possibly the single greatest cause of destructive, illegal and antisocial behavior.” (Id, p. I :20)

Eric Janus, Failure to Protect, at p. 41, expands on this, commenting:

“Difficulty controlling’ behavior is ubiquitous among ‘normal’ human beings. Many people have difficulty – serious difficulty – controlling their eating, smoking, gambling, alcohol or drug use, computer gaming, or work hours. . .. [T]he point of the ‘volitional dysfunction’ requirement is . to identify some mental characteristic of commitment candidates that distinguishes them from others. Impaired self-control does not accomplish this. The legal standards for volitional impairment are so vague that they are unlikely to provide any kind of guidance or limitation on commitment decisions.”

Eric S. Janus, “Sex Offender Commitments: Debunking the Official Narrative and Revealing the Rules-in-Use;” 8 Stanford Law and Policy Review 71, 81-82 (Summer 1997). Janus summarizes case law that, even at that early time, had already completely obfuscated the definition and breadth of application of “lack of control.”

At Footnote 168, explaining:

“In In re Blodgett the Minnesota Supreme Court set forth factors that courts should use in evaluating the ‘utter lack of power to control’ standard: “In applying the Pearson test, the court considers the nature and frequency of the sexual assaults, the degree of violence involved, the relationship ( or lack thereof) between the offender and the victims, the offender’s attitude and mood, the offender’s medical and family history, the results of psychological and psychiatric testing and evaluation, and such other factors that bear on the predatory sex impulse and the lack of power to control it.” [510 N.W.2d at 915]

“But these factors, though they may well be relevant, give no instruction about how to distinguish lack of capacity to control from failure to control. See Schopp, Robert F., Automatism. Insanity. and the Psychology of Criminal Responsibility (1991)], at 188 (criticizing Blodgett factors as being irrelevant to volitional dysfunction).”

“The Court of Appeals has not only failed to establish a workable test, it sends conflicting messages that frustrate efforts to extrapolate any coherent pattern. In some of its opinions, it has seemed to focus on impulsiveness as the meaning of ‘utter lack of power to control.’ [ citing In re Blodgett, 490 N.W.2d at 642-46.] In others the court has taken pains to explain how behavior that appears planned and deliberate can reflect ‘utter lack of power to control.'”

Footnote 170: “See In re Bieganowski, 520 N.W.2d at 530 (affirming commitment although ‘the [pedophilic] grooming process requires time, thus eliminating any ‘suddenness’ regarding the sexual activity’);

“In re Mayfield, 1995 Minn. App. LEXIS 602, at *8 (approving of expert testimony ‘explaining how planning could occur even when the person had an utter lack of control over his sexual impulses’); In re Young, 1994 Minn. App. LEXIS 1 159, at *6 (While Young may show planning and premeditation by his grooming behavior, his behavior is nonetheless impulsive and without volitional control).”

[Continuing text:] “In some cases, the court has pointed to the individual’s lack of acknowledgement that his behavior is wrong.”

[Footnote 171 :] “In In re Irwin, 529 N.W.2d at 375, the court approved of testimony indicating that:

“An important factor in determining whether one has the power to control sexual impulses is whether the person feels he has a problem; if so, he at least has some control since he knows that he is flawed, and may be more vigilant in seeking assistance … Without this basic insight, appellant has the utter lack of control required by Pearson”. See also In re Fitzpatrick, 1 994 Minn. App. LEXIS I 029, at *3 (Fitzpatrick ‘habitually shifts blame for his actions to others .. .. [and] fails to appreciate the consequences of his actions’); In re Adolphson, 1995 Minn. App. LEXIS 965, at * IO (‘ Appellant’s actions show he has no will to stop sexually assaulting adolescent males. Although appellant is aware that his conduct is against the law, he shows no remorse and expresses no second thoughts.’)

“In others, the court has found a mental disorder where ‘he knows what he is doing and that it is wrong, but he chooses to do it anyway.’ [In re Toulou, 1994 Minn. App. LEXIS I 067, at *9]…Finally, in some cases, the court has also suggested that proof that the individual’s ‘will’ is overwhelmed by strong sexual impulses [In re Kunshier, 521 N.W.2d at 882 (reciting expert testimony that ‘[Kunshier’s] impulse to rape becomes all intrusive[,] and that his ‘behavior was usually “impulse driven past any point of rational control or concern regarding negative impact upon victims or the risk of incarceration”)], or that the individual’s behavior is strongly ‘compulsive,’ points to a mental disorder [Adolphson].

In others, it is the strength of the individual’s will to have sex that provides the factual support. Frequently, what supports the finding is simply that the individual has repeatedly engaged in prohibited sexual behavior despite its consequences [In re Mattson, 1995 Minn. App. LEXIS 805, at *6 (“When a person engages in behavior despite repeated consequences, it evidences a lack of control.”)], a characterization that would apply to all repeat sex offenders.

“Even the two cases in which the court reversed a finding of ‘utter lack of power to control’ do not help develop a coherent theory. In In re Schweninger, the court reversed a commitment of a non-violent pedophile. The court clearly understood ‘utter lack of power to control’ as requiring· impulsiveness and found that the individual’s ‘planned and calculated’ behaviors were inconsistent with such a finding. [520 N.W.2d at 450 (distinguishing “plotting, planning, seductions, payments, and coercive behavior … from [an] impulsive lack of control”) The Schweninger case came directly on the heels of Linehan and appeared to be the beginning of an ‘impulsiveness’ theory of ‘utter lack of power to control.’ But the court quickly altered its course. In In re Bieganowski and a series of other cases, the court explained that planning and deliberation could be consistent with ‘utter lack of power to control.’ [citing: In re Bieganowski, 520 N.W.2d at 530; In re Mayfield, 1995 Minn. App. LEXIS 602, at *8; In re Young, 1994 Minn. App. LEXIS 1159, at *6.]

(p. 82): “In Bieganowski [ 520 N.W.2d at 530] and Mayfield [1995 Minn. App. LEXIS 602, at *8], the court decided .that ‘uncontrollability’ was consistent with ‘planning and controlled behavior.’ In addition, the court made clear that it did not have in mind any sort of internal pain or internal struggle test. In both Adolphson and Irwin, the court appears most impressed with the fact that the individuals seemed to view their deviant sexual behavior as acceptable.”

[At Footnote 198: “Thus, the following passage from the opinion: “‘[A]n important factor in determining whether one has power to control sexual impulses is whether the person feels he has a problem; if so, he at least has some control since he knows that he is flawed, and may be more vigilant in seeking assistance…. Without this basic insight, appellant has the utter lack of control required by Pearson.’ In re Irwin, 529 N.W.2d at 375; see also In re Adolphson, 1995 Minn. App. LEXIS 965.

There is no suggestion in either Adolphson or Irwin that the beliefs or desires were so irrational, as opposed to illegal and immoral, that they would satisfy a cognitive based theory of criminal responsibility. See Morse, supra:

“The underlying theory is that the consequences flowing from misbehavior are so negative and, more importantly, so patent, that all ‘rational,’ ‘volitionally able’ individuals would have avoided the misbehavior. However, there are convincing arguments that even this narrowed integrated-self test is not a meaningful account of volitional dysfunction. It is not discriminative, because virtually all repeat criminal behavior fits this test. Thus, it fails to discriminate between those who ‘could not’ and those who merely did not’ control their behaviors.” (Pg.83)

It is worth noting that some decisions of the Court of Appeals appear at least implicitly to adopt the environmental-consequences theory. These cases point out that the defendant continued to engage in criminal or anti-social activity despite numerous sanctions for his bad behavior. For example, in Patterson, the court referred, with apparent approval, to the state hospital’s report that assumed that ‘lack of power to control’ relates to choosing to commit the offenses despite negative consequences.

At Footnote 207, adding the following supporting cases:

“Similarly, in In re Sabo, 1993 Minn. App. LEXIS 947, at *3, Sabo ‘received numerous discipline violations for drug use and smuggling, verbal abuse, and threatening others,’ which supported a finding that he was unable to control his sexual impulses. See also In re Holly, 1994 Minn. App. LEXIS 715, at *5; In re Mattson, 1995 Minn. App. LEXIS 805, at *6 ( citing with approval expert testimony that ‘utter lack of control was demonstrated by the fact that even when appellant was in a structured setting, he had difficulty refraining from the use of pornography’); In re Fitzpatrick, 1994 Minn. App. LEXIS 1029, at *4 (lack of control demonstrated by ‘recent inappropriate behavior while incarcerated’); In re Patterson, 1995 Minn. App. LEXIS 1199, at *8 (offenses committed ‘despite negative consequences’ also supports a finding of ‘utter lack of power to control’).”

[Continuing text:] “If the court had hewed to this environmental-consequences test, its ‘utter lack of power to control’ jurisprudence might have had some legitimizing discriminative power. But the court’s 1995 Toulou decision [In re Toulou, 1995 Minn. App. LEXIS 623, at *7] demonstrates that the court had no such narrowed test in mind. Turning the theory on its head, the court cited Toulou’s conformance to external stimuli as the central evidence supporting the finding of ‘otter lack of power to control.’

“This analysis shows that the concept of ‘utter lack of power to control,’ as established by the Minnesota Court of Appeals, has neither discriminatory nor justificatory content. Instead, the court relies on pseudo-reasoning: statements purporting to sound like legal reasoning that are in reality tautological and hence non-explanatory.”

(pp. 83-84) “Recall that the central, and most difficult, task of the ‘utter lack of power to control’ construct is to demonstrate that a mental dysfunction legitimizes sex offender commitments. The key move is to infer mental incapacity from behavior. The philosophical theories provide rules for making that transformation, but the Court of Appeals has followed none of them.”

Consider the following, which the court has proffered as explanations of the inference from behavior to mental incapacity:

-

‘”He explained that an utter lack of control begins when the individual has an urge that cannot be delayed.’ Here, ‘experts explained how uncontrollability could occur with planning and controlled behavior.’ [In re Mayfield, 1995 Minn. App. LEXIS 602, at *4-5]

-

“‘The psychologists’ explanations show that, while Young may show planning and premeditation by his grooming behavior, his behavior is nonetheless impulsive and without volitional control in that he acts upon uncontrollable desires when presented with the opportunity to sexually abuse young girls.’ [In re Young, 1994 Minn. App. LEXIS 1159, at *6]

-

“The trial court concluded that Patterson “demonstrates an utter lack of power to control his conduct with regard to sexual matters.” In support of this finding, Dr. [M] testified that he believed that Patterson had an utter lack of power to control his sexual impulses. Once “the impulse has been created,” [M] explained, Patterson “cannot control over time the need to act upon the urge.”‘ [In re Patterson, 1994 Minn. App. LEXIS 1094, at *6]”

-

“Dr. [F] defines the term “utter lack of control” in terms of an impulse control problem in which there is an inability to stop one’s behavior despite being in an area of risk of being apprehended or caught.”‘[In re Bieganowski, 520 N.W.2d at 527]

“Though these passages have the rhetorical form of explanations, they simply replace one abstract psychological construct (‘utter lack of power to control’) with another equally opaque psychological construct (‘inability to stop,’ ‘compelled to do so,’ ‘cannot control,’ uncontrollable desires,’ ‘cannot be delayed’). They do not explain how ‘did not’ is transformed into ‘could not,’ and hence they do not perform the necessary discriminative and justificatory tasks claimed for the mental disorder element.”

Dr. Cauley testified that commitment must be limited to those who lack the ability to control their sexual actions.

“I think that is very critical in doing an assessment of risk is, does somebody have the capacity to regulate their behavior? If that is not being looked at the referral to commitment, then it has been broadened out as to who would qualify.” (Karsjens Trial Tr., v. 10. p. 2199).

In practice pursuant to said Act, authoritative Minnesota appellate decisions uphold commitment under said Act on the unscientific non sequitur that a mere records of sex crimes inherently connotes an inability to control one’s criminal sexual behavior, ignoring the unpalatable, but completely plausible alternative possibility that, on such prior sex-crime occasion(s), the person may have simply consciously chosen to commit the crime(s).

The tacit presumption by Commitment Case Defendants of inability to control one’s behavior deprives Plaintiffs of substantive due process (as well as of procedural due process; see infra) and creates an impermissible vagueness, as to utter “lack of control” or “serious difficulty” in control, against which no Plaintiff subjected to commitment proceedings can effectively defend himself.

As Warren Maas, supra at 1258, aptly sums up, “Justice Page distinguished Blodgett from Linehan II on the basis of the intentional absence of a volitional control element.” Additionally, decisions of the Minnesota Court of Appeals have respectively held that (a) pedophiles are inherently at a very high risk of reoffending; and (b) extra familial pedophiles are inherently at an even higher risk of reoffending. This effectively equates a past record of any such offenses with satisfaction of either the SDP or SPP standard for commitment. By applying either of these holdings to Plaintiffs with such criminal records, Commitment Case Defendants deprive Plaintiffs of substantive due process.