If you ask John Q. Public about the public safety risk posed by a juvenile who has been arrested for a sex offense, chances are he will estimate too high. The public is woefully uninformed when it comes to risk of sexual reoffense in general, and nowhere is the gap between reality and media-driven anxiety wider than in the case of juvenile sex offenders.

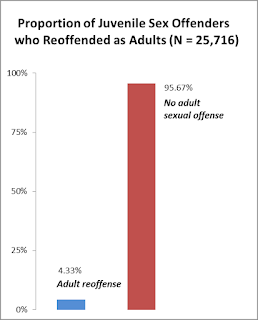

Michael Caldwell, a prominent expert on juvenile delinquency at the University of Wisconsin in Madison, has decided to take the bull by the horns and nail down an accurate risk estimate. His goal is to collect and analyze every single study that exists, whether from peer-reviewed and published research or government studies. So far, he’s put together an impressive 88 data sets comprising a whopping 25,716 juvenile sex offenders.*

The data are remarkably consistent: Overall, people who committed a sex offense prior to age 18 have less than a 5% risk of being arrested or convicted for another sex offense as an adult.

Although the average followup period in these 88 studies was more than five years, Caldwell says the length of the followup isn’t as critical as you might think. That’s because risk is highest in the months immediately following the last offense, and plummets dramatically as time goes on.

That’s not surprising, given what we know about adolescent immaturity. Juvenile sex offenders are plagued by raging hormones, poor impulse control, and even poorer judgment. Often, their sex offending is part of a broader pattern of general delinquency that includes behavior like stealing, truancy, fighting, rule-breaking and drug use.

But perhaps more remarkable than their low risk for sexual reoffense as adults is the finding by other researchers that most adult men who are arrested for committing sexual offenses were never part of this juvenile sex offender pool in the first place.

In other words, there’s a good chance we are looking at apples and oranges — that most juveniles who are arrested for a sex offense are just screwed-up kids, rather than budding pedophiles or preferential rapists like some adult offenders.

Are juvenile sex offenders special?

Indeed, many scholars of delinquency are coming to the conclusion that the “juvenile sex offender” – a category that has come into vogue largely due to growing interest in adult sex offending over the past couple of decades – may not actually exist as a distinguishable entity.

That would be very good news from a public safety standpoint, because the majority of young people who get into trouble with the law gradually cease offending and fade into the carpet of the community as they mature and settle down into their adult lives.

Amanda Fanniff, of Palo Alto University’s Juvenile Forensic Research Group, is one such scholar. She is testing the uniqueness of juvenile sex offenders by comparing them with other delinquent boys from the federally funded Pathways to Desistance project, a large-scale, multi-site, longitudinal study of serious juvenile offenders in Arizona and Pennsylvania.

So far, Dr. Fanniff has not found much to distinguish the 127 boys with sex offenses from the 1,021 boys with serious non-sexual crime, in terms of measurable things like school problems, parental pathology, antisocial history, or deviant peers.

If anything, based on followup periods averaging about seven years, the juveniles who offended sexually have lower risk of both general and sexual recidivism than the other delinquents, she reported this week to a meeting of the California Coalition on Sex Offending.**

Consistent with other research, Fanniff found that in sheer numbers, more of the juveniles without a prior sex offense case picked up a sex crime as an adult. Out of the 1,148 boys she tracked, 10 sex offenders and 29 general delinquents were arrested for a sex offense during the average 7-year followup period. Because there were far more general delinquents overall, that translates to a sexual recidivism rate of about 8% for the juvenile sex offenders, and 3% for the other boys, or about 3% overall. (See chart, left. The fact that her juvenile sex offenders recidivated at a slightly higher rate than Caldwell’s aggregate average likely owes to the small size of her sample, 127 versus his vast pool of 25,716.)

If the perception of uniqueness is just a projection of the beholder’s, says Fanniff, we might do better to focus on treatment programs that are proven to work for delinquents, such as multisystemic therapy that targets family and community variables, rather than focusing too heavily on sex offender-specific treatment with its uneven track record and sometimes-counterproductive methods.

What this growing body of research evidence tells us, agree Fanniff, Caldwell and other researchers such as Jodi Viljoen at Simon Fraser University in British Columbia and her colleagues, is that it is extremely hard to accurately identify a juvenile sex offender who is going to reoffend.

The task is so hard, indeed, that even risk assessment instruments designed specifically for this population – like the ERASOR and the J-SOAP – are doomed to fail most of the time.

But from a purely statistical point of view, prediction is actually a no-brainer:

If you bet that any juvenile sex offender is NOT going to reoffend, you will be correct 95% of the time. It’s pretty doggone hard to improve on that good news.

*These new data are not yet published. Dr. Caldwell’s 2010 review article in the International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology found the same pattern, but with only 66 data sets comprising about 11,000 offenders.

**Dr. Fanniff’s study has been accepted for publication in the Temple Law Review. In the meantime, you can request information from her via email.

Go to Source

Author: Karen Franklin, Ph.D.

The opinions expressed within posts and comments are solely those of each author, and are not necessarily those of Just Future Project.